I’d like to be able to claim that this list is so long because I had so much down time this year in particular, but I actually watched more movies in 2018 than I did in 2020. I’ll try to keep each entry as mercifully short as possible, and keep in mind that this ranking is essentially meaningless. New movies (i.e. movies from the last 3 or so years) and rewatches aren’t counted.

100. You Are Not I (Sara Driver, 1981)

A ghostly, affecting little mini-feature from the great downtown filmmaker, co-written and shot by Jim Jarmusch. Pair with “Possibly in Michigan” for a double feature of feminist parables in an eerie, liminal Midwest.

99. Rancho Notorious (Fritz Lang, 1952)

“Fritz Lang Western” are not three words that should go together, but Fritzi channels his natural unsuitability for the genre into a bizarre, proudly artificial power struggle helped immeasurably by Gods Dietrich and Arthur Kennedy. This won’t be the last we see of Lang.

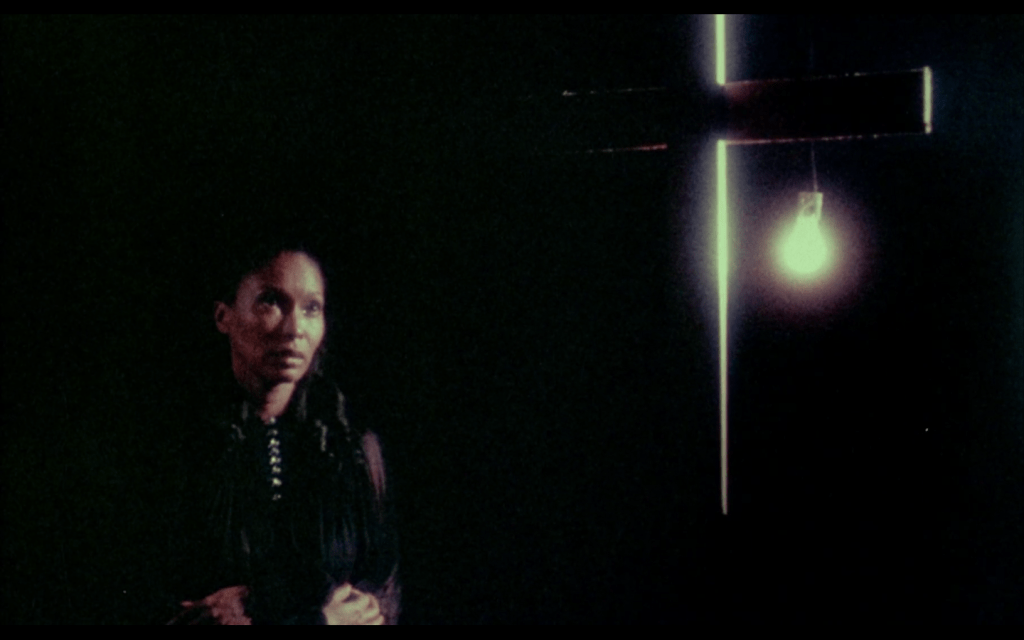

98. Ganja and Hess (Bill Gunn, 1973)

A heady inquiry into the legacies of colonialism, Christianity and the class system and how they organize and stratify Black life in America, all wrapped up in that most metaphorical of horror genres, the vampire film. About 20 minutes too long but Bill Gunn was something else.

97. Safe in Hell (William Wellman, 1931)

The first Pre-Code to appear here, but not the last. Wellman brings his talent for imposing compositions and desperate atmospheres to a deliciously lurid story, headlined by the great Dorothy MacKaill. Basically heaven.

96. One Way Passage (Tay Garnett, 1932)

Speaking of Pre-Code and heaven, I could have gone either way including this or Jewel Robbery, another insanely sexy William Powell/Kay Francis vehicle. I went with this one because of its greater emotional force, but watch these movies and tell me there’s more sex in the cinema today (or, really, ever) than there was in 1932.

95. Deathdream [aka Dead of Night] (Bob Clark, 1974)

You know a movie is great when it owns despite like 80% of the shots being completely out of focus. Seriously, it seems like if you didn’t touch the focus at all you’d do better than they did on this out of pure chance. Anyway, a very disturbing and heartbreaking proto-slasher about the monstrosity that is American imperialism coming home and doing what it does best: killing.

94. Raining in the Mountain (King Hu, 1979)

“King Hu heist movie starring Hsu Feng” feels like something I could only dream about, but here it is in all its glory. This is admittedly my least favorite King Hu film that I’ve seen, but that’s like saying which of Beethoven’s symphonies is your least favorite.

93. Horse Feathers (Norman Z. MacLeod, 1932)

Pure joy. This starts as most Marx Brothers movies do, with the boys dressing down a given stuck-up institution (in this case a college) with their various spoofs and goofs. The fact that it eventually builds to the much more chaotic milieu of a football game, which Harpo then also manages to destroy, feels like the brothers upping the ante.

92. Day of the Dead (George Romero, 1985)

Romero suggests that the scariest thing about the apocalypse will be having to rely on the bigoted, authoritarian fascists populating the military, whose capacity for violence might be our only hope for protection but will inevitably be turned against us, and which probably caused the apocalypse in the first place. I’m a particular fan of the guy whose screams get higher in pitch as his vocal cords are ripped out.

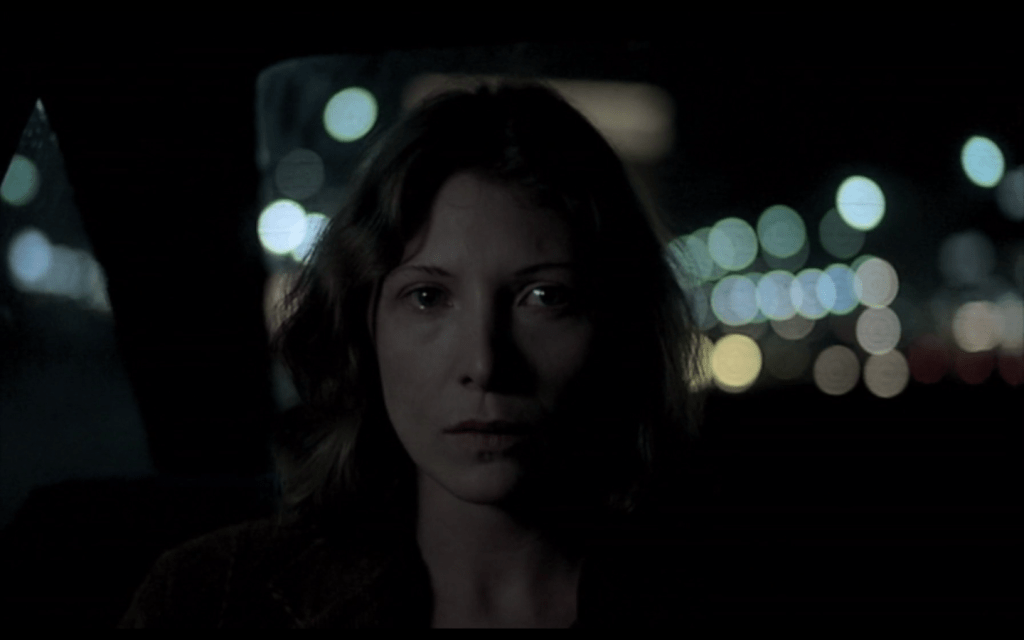

91. The Passenger (Michelangelo Antonioni 1975)

Probably the film on here I understand the least, but it hits hard anyway. Really have no idea what to write about this one, so let’s move on.

90. Within Our Gates (Oscar Micheaux, 1920)

I get the impression that this film is seen as important and impassioned but unsophisticated, which is bullshit; the multivalent exploration of tensions within the Black diaspora across class and geography here are incredible. The DJ Spooky score is incredible.

89. The Crazies (George Romero, 1973)

Our first repeat director being Romero is fitting. Difficult to say anything about this one that hasn’t been made exceedingly obvious by the past 9 months, other than to say that this dude saw the future like few others have. Rough around the edges, but brilliant accumulations of detail.

88. Of Time and the City (Terence Davies, 2008)

A bitterly funny and deeply moving essay film by possibly my favorite working filmmaker, one that I’ve been meaning to see for years. An important reminder that “Dirty Old Town” is one of the greatest songs ever written.

87. The Wedding Night (King Vidor, 1935)

I watched this early in the year but I’m writing this as The Great New York Snowstorm of 2020 begins and it’s making me want to revisit this movie’s snowed-in, candlelit vibe. Vidor is well-represented on this list, so suffice it to say that this is one of his most tender, beautiful and underappreciated films. Anna Sten shoulda been way bigger.

86. Hail Mary (Jean-Luc Godard, 1985)

The final stretch of this movie is among the most bracingly intimate and sincere grasps toward transcendence in cinema. I don’t know how successful the rest of the movie is, but that’s one of those next-level passages that only Godard can conjure up.

85. Crimson Tide (Tony Scott, 1995)

Ashamed to say I was a Tony Scott skeptic as recently as last year. Is it possible I’m overrating this because of how much I miss action movies with real actors, colors and compositions? Yes. Is it also possible that those kinds of action movies rule, and as such I’m rating this correctly? Almost certainly.

84. Matewan (John Sayles, 1987)

Speaking of possibly overrating things because of how directly they appeal to me, my head agrees with some of Dave Kehr’s criticisms of this movie. My heart, however, realizes that it’s a leftist pro-labor movie with a great cast of dudes, Appalachian folk songs and gorgeously rustic Haskell Wexler images that feel impossibly authentic.

83. Les Rendez-vous D’Anna (Chantal Akerman, 1978)

A tour through late-70s Europe, examining how the horrors of the early and middle 20th century gave birth to nothing more than the loneliness and boredom of its later years. Severely depressing but brilliantly executed.

82. Street Scene (King Vidor, 1931)

An antecedent to Do The Right Thing, with the roiling ethnic and social tensions across one day on a microcosmic New York block inevitably leading to tragedy. Like Spike Lee, Vidor’s warmth towards his characters and subtly effective visual strategy make the potentially schematic setup feel incredibly organic.

81. Knockabout (Sammo Hung, 1979)

The relative obscurity of this is baffling to me, as it strikes me as one of Sammo Hung’s most joyful, efficient, brilliantly constructed films. The lack of Jackie Chan probably doesn’t help, but I’ll take this over Wheels on Meals any day.

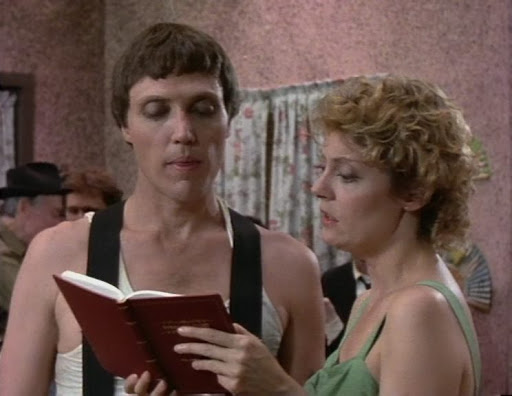

80. Who Am I This Time? (Jonathan Demme, 1982)

This made-for-PBS adaptation of a Kurt Vonnegut short story is riddled with narrative and emotional shortcuts, but it’s hard to care about that much in the face of Jonathan Demme’s irresistible playfulness and emotional dexterity (not to mention the trio of Christopher Walken, Susan Sarandon and Robert Ridgely).

79. Punishment Park (Peter Watkins, 1971)

As effectively brutalizing a portrait of the police state as you’re likely to find, in no small part because Watkins suggests the utter incapability of the left to meaningfully fight it. Few films achieve its mix of pure righteous anger and conflicted political discourse.

78. The Strawberry Blonde (Raoul Walsh, 1941)

I don’t think this is an original thought on my part but it’s fascinating to look at this as a counterpart to Walsh’s The Roaring Twenties, both melancholic, nostalgic, “mature” looks back at genre heydays whose characters share Walsh’s point of view. TBH I have no idea why Cagney would prefer Rita Hayworth over Olivia de Havilland to begin with.

77. The Masque of the Red Death (Roger Corman, 1964)

Another plague movie, another challenge to find original things to say. Actually, as I’m writing this I think this movie should be rated lower on here, but dope colors, Satanic sex cults and Vincent Price go a long way. Both an Epstein AND a COVID movie.

76. This Land Is Mine (Jean Renoir, 1943)

What looks on the surface like Sorkinesque epic lib logic ownage actually becomes a complex, moving treatise on the true meaning of resistance in the hands of Renoir, screenwriter Dudley Nichols and Charles Laughton. I’m a sucker for movies about weak, frightened men (e.g. Scarlet Street) and Laughton’s here is one of the greatest.