If you read the first entry of this list, I commend you for sticking with me! If you didn’t, you didn’t miss much. I realize I didn’t say this in the last entry, so here goes: I promise not to couch any of this in extremely cliched “omg 2020” sentiments. I’m sure you’ve had your fill of those, and if you haven’t, try looking literally anywhere else on the Internet. We’re here to talk about one thing, and that’s movies, goddammit.

75. The Swimmer (Frank Perry, 1968)

An essential entry in the “everyone from Connecticut is psychotic” canon.

74. Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable (Shunya Ito, 1973)

The truly disturbing acts of sexual violence and apocalyptic world Ito creates only makes his eventual tale of solidarity that much more beautiful and radical. Everything from the abortion to firebombing the sewer is pretty much perfect and the image of the falling matches is an all-timer. God Meiko Kaji.

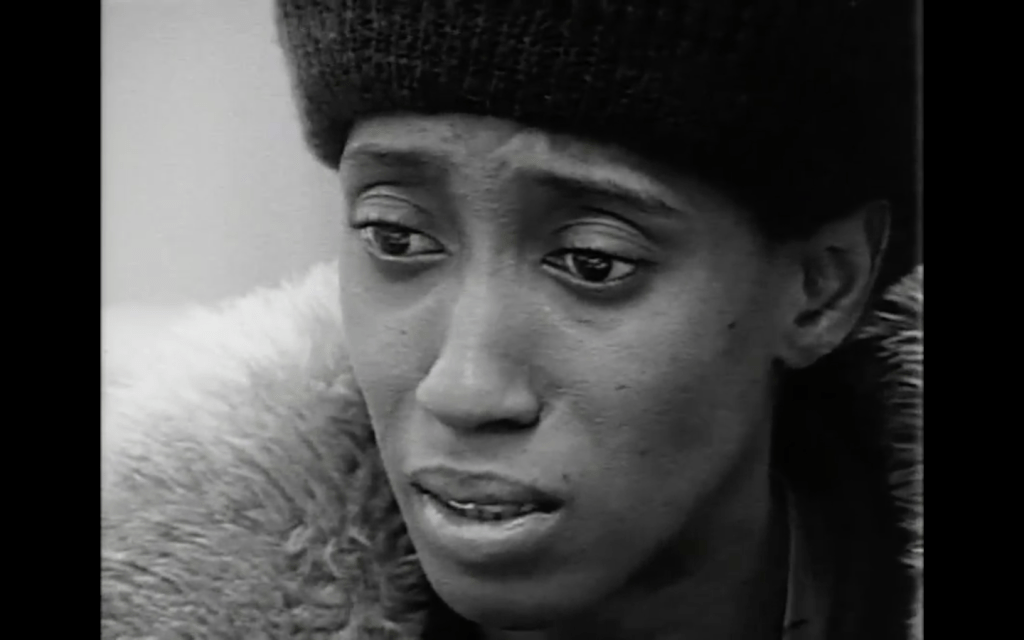

73. Bless Their Little Hearts (Billy Woodberry, 1983)

Like the first movie on this list (You Are Not I), this was written and shot by a more famous auteur (in this case Charles Burnett), but it would rank very highly in that filmmaker’s body of work anyway. These are vital, unrepeatable images and performances from one of American cinema’s most essential wellsprings.

72. Showgirls (Paul Verhoeven, 1995)

Only a man like Paul Verhoeven, who openly delights in the worlds of sex, sleaze and vice in a way few of us could ever imagine, could make an entire movie about how those worlds have been ruined by gaudy commercialism. Fuck “so bad it’s good.” It’s good.

71. Island of Lost Souls (Erle C. Kenton, 1932)

The madness of the white man’s burden. There is, as the kids say, a lot going on here- its various (sometimes troubling) threads of colonialism, fear of/exoticized attraction to the racial other, and God complexes could support a PHD dissertation. Luckily, in the ’30s they knew to wrap these ideas in lowbrow horror movies, so it doesn’t feel like one.

70. The Naked Spur (Anthony Mann, 1953)

I’ve taken a blasphemously long time to come around to Anthony Mann, but this one, for me his best Western in a walk, is undeniable. A web of moral, strategic and emotional maneuvering set against some of the best location shooting this side of Monument Valley.

69. Day of the Outlaw (Andre de Toth, 1959)

The second sentence of the above entry applies here too, but in de Toth’s unforgiving hands this achieves a brutality that few horror movies can aspire to. The scene where the outlaws force the town’s women to dance in place of raping them is physically painful to watch. A world at absolute zero, without one atom of warmth. Burl Ives is a long way from Sam the Snowman.

68. Center Stage (Stanley Kwan, 1991)

I had a tough time with this one- its recreations of Chinese silent movie star Ruan Lingyu’s life are so closed-off, so deeply artificial, so devoid of character psychology, that it would be easy to call this a failure as a biopic. But as the inclusion of scenes depicting the film’s director and stars discussing and making the picture indicate, that’s just the point- to illustrate her ultimate unknowability, the way that she was trapped in the melodrama that had been made of her life during her own time.

67. Welfare (Frederick Wiseman, 1975)

It’s difficult to see how someone could be familiar with Wiseman’s work and not come to the conclusion that he’s one of the most important American artists. That being said, it’s probably reductive to lob the title of “important” at him like everyone else, and it discounts how intense an emotional experience his films can be, this one in particular.

66. Kiki’s Delivery Service (Hayao Miyazaki, 1989)

I should have seen this a long time ago. It’s pretty much impossible to imagine any mainstream American animated movie featuring something like the scene where a thoroughly dejected Kiki wordlessly lies in her bed and Miyazaki just patiently stays with her.

65. Two Weeks In Another Town (Vincente Minnelli, 1962)

Better than The Bad and the Beautiful. There, I said it.

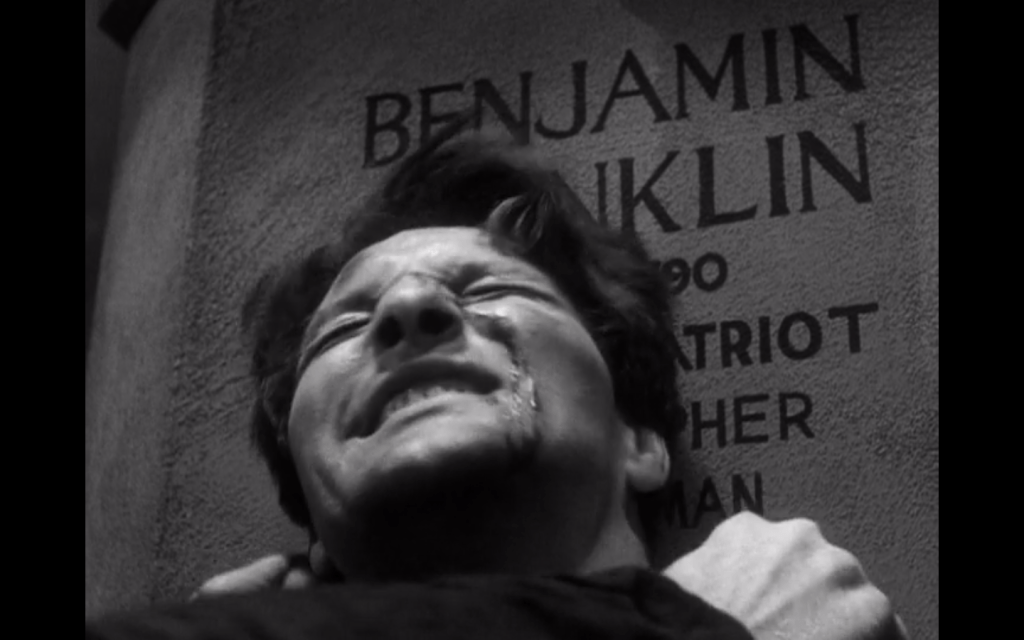

64. Park Row (Samuel Fuller, 1952)

Lives on the dichotomy between the lofty ideals of journalism and the dirty, physical work of doing it; whether manufacturing stories or the papers themselves, the attention to the procedural exigencies of publishing a newspaper here is astounding. The speechifying that expresses the former can hold the film back, but any trace of piousness is obliterated by the thrillingly forceful direction that embodies the latter. Fuller achieves a brilliant sense of place and history, a charged atmosphere that extends to every element of the m-e-s.

63. The Party (Blake Edwards, 1968)

The elephant in the room here (aside from the actual, you know, elephant in the room) is Peter Sellers in brownface. It’s not cool, but it would a mistake to say that Edwards treats Hrundi V. Bakshi as the bumbling fool he initally appears to be- he ultimately emerges, far more than any of the Hollywood types in the picture, as a person of quiet dignity and intelligence. Like Keaton and Chaplin, it constructs a space that doubles as a sight gag machine and a baffling, hostile foreign world.

62. Honkytonk Man (Clint Eastwood, 1982)

From what we know about Clint’s forthcoming Cry Macho, it appears to be, along with this and A Perfect World, his third film in a trilogy of road movies about doomed men teaching boys the hard lessons of life. Needless to say, I’m very excited.

61. The Hole (Tsai Ming-Liang, 1998)

Going into this year, Tsai Ming-Liang was probably the most internationally acclaimed filmmaker I had never seen anything by. I’ve now seen 7 of his films, the most I watched this year by anybody, and it could be 8 if I get around to Days at some point before New Year’s. Anyway, this was my second-favorite of the lot (we’ll get to my fav), and the THIRD plague movie on this list so far. Are there any more? If you’re brain-damaged enough to still be reading, you might as well read on.

60. Top of the Heap (Christopher St. John, 1972)

I was incredibly glad to see this movie get a mini-moment in the sun (on Film Twitter, at least), because 1) it got me to see it and 2) it’s incredible. A furious, wildly imaginative report from the frontlines, taking the form of a conspiracy thriller where its delusional protagonist realizes the conspiracy (in this case, the institutional racism his police badge doesn’t exempt him from) goes all the way to the top.

59. Déjà Vu (Tony Scott, 2006)

I’m man enough to admit that I did not think Tony Scott was capable of synthesizing Laura, Vertigo, and Strange Days into a new technological milieu that forecasted the end of Twin Peaks: The Return. Scott’s information overload style has never served his material better, and it results in some unforgettable images and sequences. Like Michael Mann, Tony was a romantic at heart who was all about finding the moments of connection amidst these hyperreal digital worlds, and this is as romantic as it gets.

58. Portrait of a Young Girl at the End of the ’60s in Brussels (Chantal Akerman, 1994)

Now that I’m looking at it, I believe Akerman and King Vidor are tied for the most entries on this list with 3 apiece (they both have one more coming up). Her direction here- precise yet inviting, constantly recalibrating the relationship between main character Michele and the spaces around her, is astonishing.

57. Pyaasa (Guru Dutt, 1957)

Pretty much nonstop virtuosity, with a brilliant, breathless sense of space and incredible expressionist lighting and compositions. Dutt eventually goes a little overboard, both stylistically and with the preachiness of his message, but this is an incredible achievement.

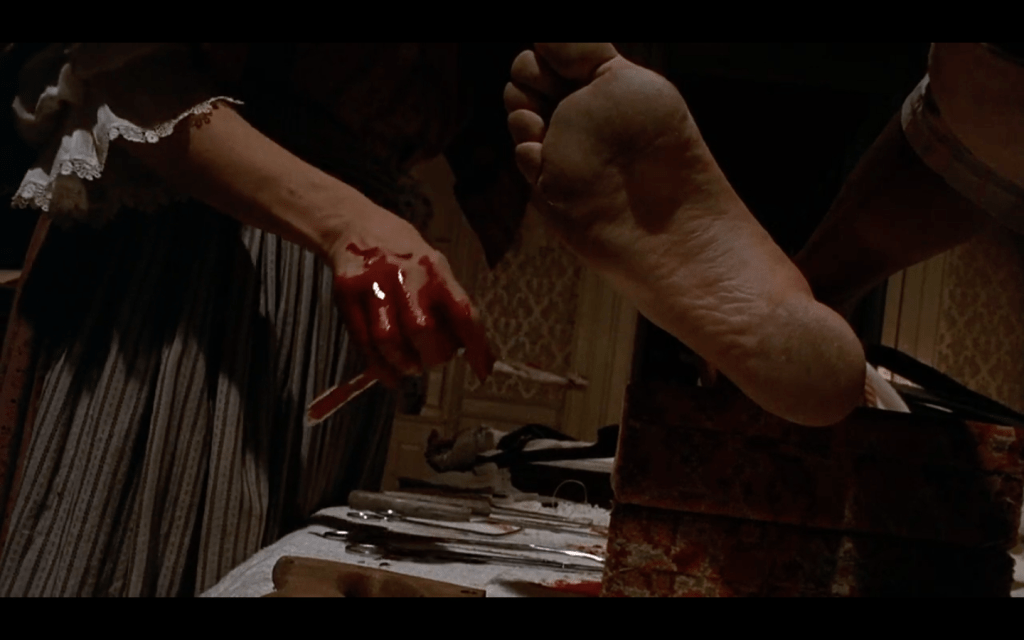

56. The Beguiled (Don Siegel, 1971)

I think Sofia Coppola’s adaptation has its strong points, but her inability to tap into what this story requires- a genuinely mad, perverted point of view- is what makes this so much more effective. Rather than sit back and take a dour, distant view of the women as porcelain figurines, Siegel dives headlong into their psychosexual hangups with no concern for good taste.

55. Drunken Master (Yuen Woo-Ping, 1978)

The spiritual and political dimensions of martial arts are replaced with broad comedy and almost nonstop action, but the direction here is so forceful and precise, the choreography so personal in its complexity, that the results are no less thrilling. A vision of a popular cinema of anything-goes energy, where a Scooby Doo-esque real estate development plot can be introduced out of nowhere and immediately forgotten 90 minutes in with no harm done. There’s something so wonderful about suggesting that the key to martial arts isn’t inner peace or spiritual transcendence, it’s getting shitfaced. One of the most purely enjoyable films ever made.

54. Our Daily Bread (King Vidor, 1934)

Replacing ideology with action- never mind that that action is itself ideological. One of the most beautiful and radical visions of community ever filmed, a full-fledged portrait of anti-capitalist solidarity on the most modest and human of terms. The justly celebrated final montage takes Eisenstein to a sacred yet wholly physical place; the entirety of political struggle sublimated into a woman replacing a faltering man in the shovel line, the earth that they sow floating up like their spirits transcending the limits of this mortal plane.

53. The Tarnished Angels (Douglas Sirk, 1957)

I’ve now seen Robert Stack in five films- Airplane!, To Be or Not to Be, The Mortal Storm, Written on the Wind and this. He’s played a pilot in four of them. Dude loves planes!

52. Steamboat Round the Bend (John Ford, 1935)

Ford’s ability to suggest cuttingly satiric and bitter undercurrents while working in such a warmly comedic register is remarkable. Its genuine nostalgia for a bygone era is constantly tempered by poking fun at the Southerners’ gullibility towards tent-revivalist hucksters and preachers, so long as they’re plied with laughable images of their rebel heroes. Darker still is the treatment of Duke’s execution, which everyone in a position of power seems to understand is unjustified, yet is responded to with callous shrugs at every turn. Embodying the whole spectrum is Rogers, of course, who radiates with the genial warmth that defines the film yet brilliantly shades his character with an essential loneliness. I’ve made this all sound too dark- it is truly a joyful experience, and that Fordian blend of tones, contradictory in theory but sublime in the master’s execution, is what makes it so special.

51. Local Hero (Bill Forsyth, 1983)

Another movie that’s had a big moment this year, in this case because of a Criterion release, and seemingly every single person on Film Twitter has gone on record with how deeply they love this movie and how they can’t imagine anyone not loving. And… yeah. It’s hilarious and sad and insightful and surprising, but most of all it conjures a subtle magic around its edges that’s like nothing I’ve ever seen.