We’re getting into serious masterpiece territory with most of these, folks. As such you should remember not to put much stock into these rankings- even I’m looking at them with a certain amount of disbelief (#46 should be higher, you moron!). Just take my word, they all kick ass.

50. Golden Eighties (Chantal Akerman, 1986)

Should be discussed a lot more in conjunction with Johnnie To’s Office– both musical satires that use highly theatrical, brightly-colored recreations of soul-sucking capitalist institutions to point out that even the fantasies of the movies can’t offer a real escape.

49. Strange Cargo (Frank Borzage, 1940)

This Christian allegory from the ultimate romantic Frank Borzge gets a little blustery by the end, but it’s extraordinarily complex and sensitive, with a brilliant sense of atmosphere, the interactions of its violent men and most importantly of the unknown. At every moment the film feels the opposing pulls of sin and salvation, and what makes it great is that Borzage delights in the plesaures of both. It’s conservative, maybe, but hardly sanctimonious.

48. Mr. Arkadin (Orson Welles, 1955)

Christopher Nolan should watch this to learn how to make a movie that’s 90% exposition sing. An update to Citizen Kane that moves the focus from the hollow corruption of American’s pre-war masters to the clandestine evil that gave birth to the postwar international ruling/criminal class.

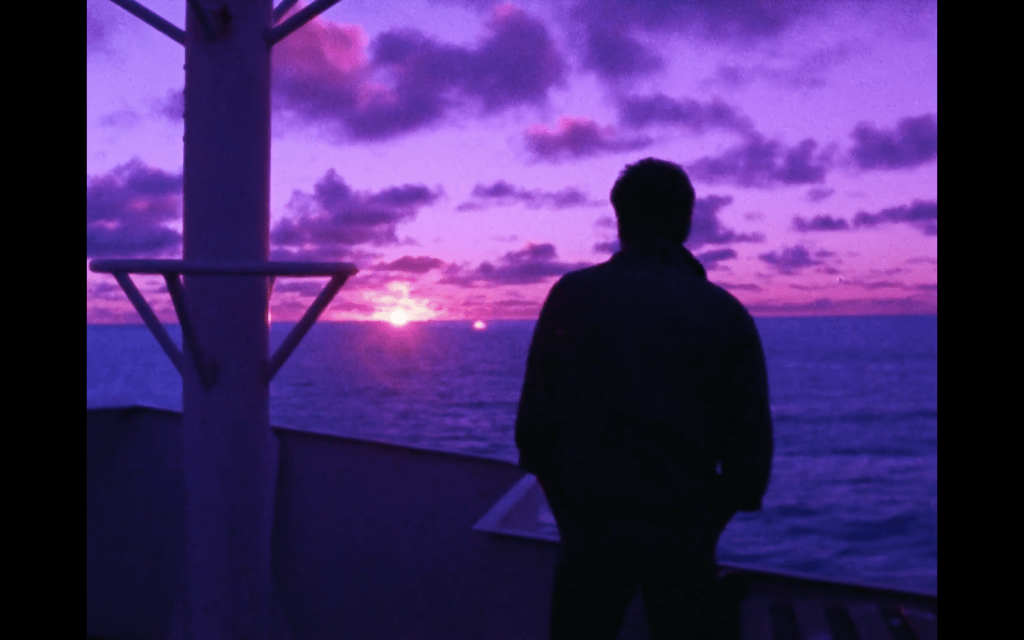

47. Three Crowns of the Sailor (Raul Ruiz, 1983)

Had to put this together with Arkadin, because I watched it right after Mank and one feels Welles’ (particularly ’50s Welles) presence here far more. Ruiz shares Orson’s dazzling-but-dingy visual style and fascination with fiction, while adding a very personal and autobiographical melancholic touch to his story of dislocation and loss.

46. Lola (Jacques Demy, 1961)

Like one of those 2000s-era “hyperlink narrative” movies but good and incredibly moving. Anouk Aimee is surreally gorgeous.

45. Touki Bouki (Djibril Diop Mambéty, 1973)

A movie that resists Western colonial encroachment while also acknowledging its temptations in its very form. Remarkable and very funny.

44. U.S. Go Home (Claire Denis, 1994)

The two most famous episodes of the French anthology series Tous les garçons et les filles de leur âge are now both represented on this list, this one a sadder (and better, sorry) Lovers Rock that morphs into a cautionary tale about why you should never hang out with Vincent Gallo.

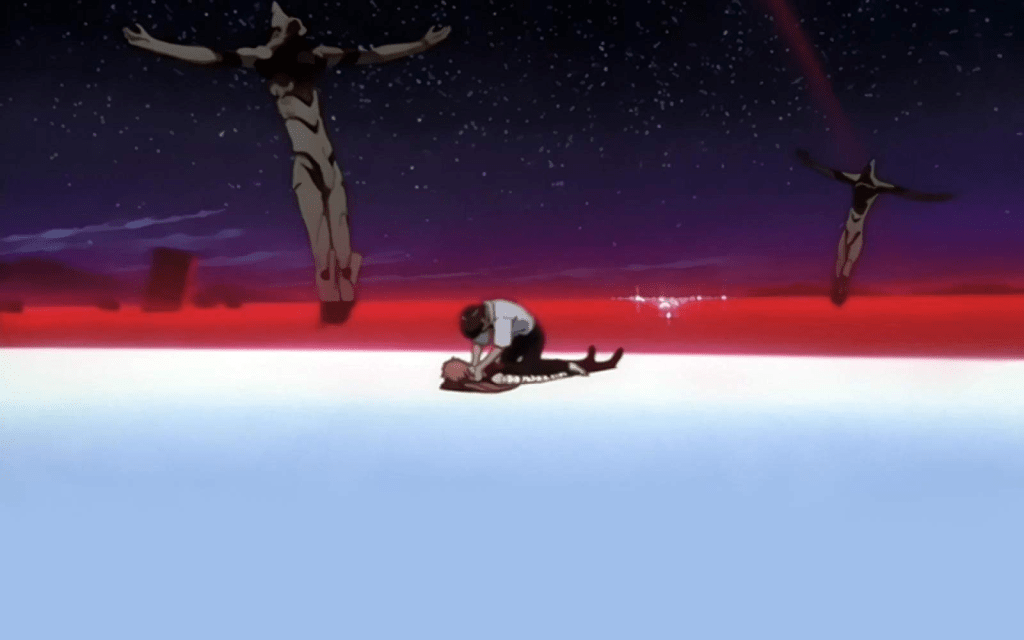

43. Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion (Hideaki Anno, 1997)

A brain-meltingly intense and assaultive experience that concentrates into a very simple story about choosing to believe in people no matter how much agony they’ve caused you. Can kind of only be experienced, not written about.

42. Bad Black (Nabwana I.G.G., 2016)

The finest export of Ugandan action movie hub Wakaliwood, and the most purely joyful experience I had watching a movie this year. As inspiring a wellspring of creativity, wit and passion as I’ve ever seen, all made for a fraction of the lunch budget on a single day of shooting a Marvel movie. Any time you want to believe that cinema will never die, watch this movie.

41. Dusty Stacks of Mom: The Poster Project (Jodie Mack, 2013)

Continuing on the theme of “inspiring wellspring[s] of creativity, wit and passion,” this stop-motion experimental collage film scored to one-woman filmmaking team Jodie Mack’s own narration, sung to the tune of Dark Side of the Moon over an 8-bit synthesizer playing the same, is a work of impossibly potent imagination. Mack brings a melancholic humor to the tale of her mother’s poster store going out of business in the face of Amazon, recognizing both the frequent tackiness of the images she sells (like Dark Side) and their genuine meaning in people’s lives and identities.

40. The Wind (Victor Sjöström, 1928)

Lillian Gish, in her last silent role, deepens Sjöström’s simple allegorical tale with shades of complexity only the greatest actors can reach, especially when doing so without the benefit of dialogue.

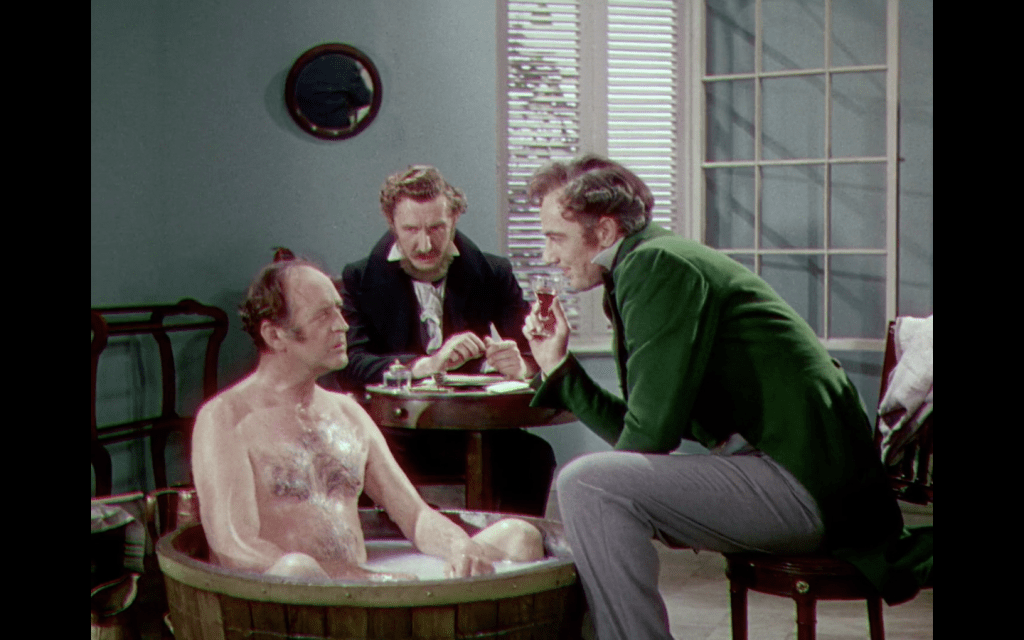

39. Under Capricorn (Alfred Hitchcock, 1949)

Probably the most underseen and underrated of Hitchcock’s films, this finds the master developing and deepening the extremely long takes and mobile camera he experimented with in the previous year’s Rope to newly expressive ends. Watching this should dispel any notion of Hitchcock as being closed off to emotion or uninterested in actors. Hostile? Yes. Contemptuous? Yes. Abusive? Certainly. But uninterested? Never.

38. Street Angel (Yuan Muzhi, 1937)

I regret watching this on a shitty YouTube transfer, which left me wondering how much the shadows of its Shanghai back alleys would deepen the story. Still, this early Chinese sound film is plainly astonishing, a blend of teenage romance, tragic melodrama, progressive social picture, crime film and musical that feels decades ahead of its time.

37. Femme Fatale (Brian De Palma, 2002)

For the first half an hour or so I thought that I might actually have been watching the greatest movie ever made. De Palma uses every formal trick up his sleeve for a ludicrously enjoyable half-hour setpiece of pure movement, rhythm and danger. It’s like the visual equivalent of a Mozart symphony, if Mozart symphonies featured hot babes making out and stealing diamonds at Cannes. The rest of the movie can’t possibly live up to it, but it’s all great, and the eventual, inevitable twist is so hilariously stupid that I have to believe it’s a classic De Palma troll. He dares you to get upset about breaking narrative rules and logic, and you do. The chad De Palma vs. the virgin movie viewer.

36. New Rose Hotel (Abel Ferrara, 1998)

I can’t claim to understand this movie, but I felt it. A scif-fi espionage thriller with all the sci-fi, espionage, and thriller elements taken out, so all that remains is Christopher Walken, Asia Argento and Willem Dafoe sitting around in lushly appointed rooms talking about… I don’t really know what. All I can say is that Ferrara saw the 21st century in all its soul-crushing anesthetized isolation, corporate dominance and vicarious screen-life with frightening clarity.

35. Strange Days (Kathryn Bigelow, 1995)

This and New Rose Hotel make for another great double-feature pairing (you could even throw in Femme Fatale as well), in this case for two end-of-millennium sci-fi thrillers where the greatest terror in the future is the panopticon, both eliminating privacy and making everyone anonymous. Bigelow’s direction is electrifying throughout, and though the revolutionary potential of its killer cop conspiracy storyline is ultimately ditched in favor of a “few bad apples” resolution, it remains highly rated on here only partly because it’s the last movie I saw in a theater before you-know-what.

34. Faust (F.W. Murnau, 1926)

First half is one of the most relentlessly astonishing achievements in cinema, and even if parts of the second half feel more suited to the severe moral vision and capacity for capturing human evil of a Fritz Lang (who certainly would have cut down on some of the dumb comedy), the sublime romanticism of the ending is pure Murnau.

33. Buffalo ’66 (Vincent Gallo, 1998)

Cannot believe I went 23 years without this movie in my life. Diseased Upstate New York/Great Lakes Brain, the existential agony of Bills fandom, Kevin Corrigan playing a guy named “Goon,” exactly two minutes of Mickey Rourke, a Ben Gazzara musical number… folks, it speaks to me.

32. The Goddess (Wu Yonggang, 1934)

What can you say about something this pure, this devastating? Sometimes movies don’t need explaining.

31. Ornamental Hairpin (Hiroshi Shimizu, 1941)

If the central romance here was more developed I would be talking about it as one of the greatest movies I’d ever seen. Japanese directors get compared to each other rather than talked about on their own terms too much, but seeing as this is the only Shimizu film I’ve seen, I’ll say it’s a perfect synthesis of Naruse’s delicate serenity and Mizoguchi’s unbearably concentrated emotions and camera moves.

30. There’s Something About Mary (Bobby and Peter Farrelly, 1998)

All the narrative precision, warmth and inspired slapstick bravado of Preston Sturges in service of one of the movies’ most hilarious and laser-accurate dissections of male desire. Basically perfect but for the appearance Brett Favre. Words fail when you’re faced with something like a final shot of a sniper taking out Jonathan Richman, all you can do is marvel at the miraculous dream machine that is the cinema.

29. Gohatto (Nagisa Oshima, 1999)

Much like Golden Eighties and Office, I’m shocked I haven’t seen this compared to Claire Denis’ Beau Travail– both 1999 films that feature a young, gifted entrant in a military force who sets off a whirlwind of jealousy and queer desire among others in the group. Who knew that late-Edo period samurai cops were so down with homosexuality?

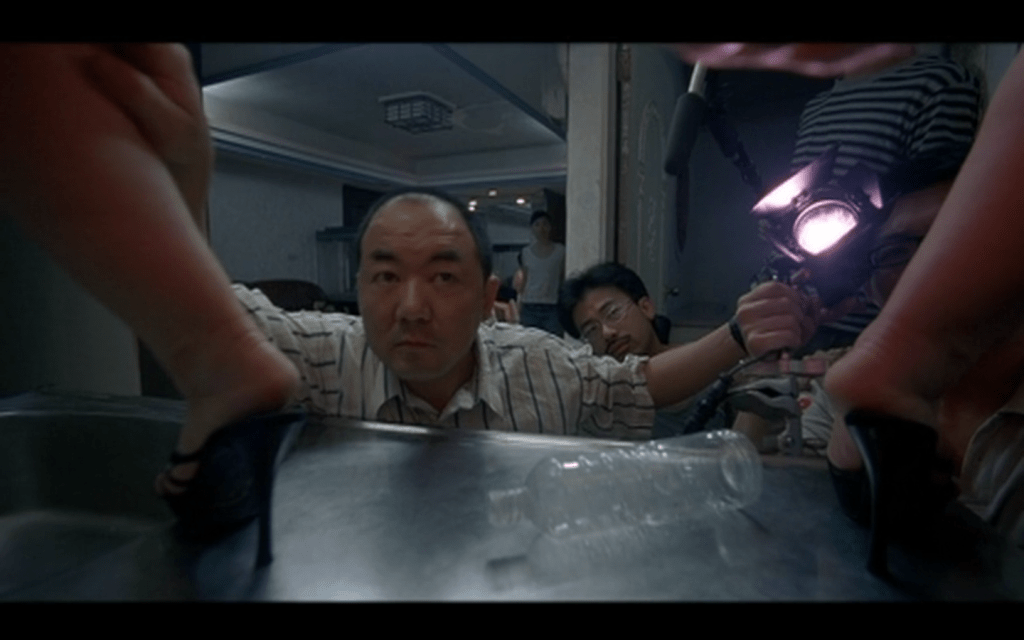

28. The Wayward Cloud (Tsai Ming-Liang, 2005)

The crown jewel of my introductory Tsai marathon this year. While this is technically a sequel to What Time Is It There?, the musical numbers and slight sci-fi bent mark it as a companion piece to The Hole, my other Tsai favorite. This is both his scariest and funniest movie, culminating with a sequence that genuinely shocked me more than anything else I saw this year. The kind of movie that even a great filmmaker can only make once in a lifetime.

27. The Human Factor (Otto Preminger, 1979)

I’d heard a lot of good things about Otto Preminger’s final film from trusted sources, but still went in expecting a bit of a slog (“the dullest movie ever made”- Rex Reed). What I got was a crushing catalog of loneliness, numbness, boredom and desensitization feeding a liberal order that wantonly metes out violence and misery at home and abroad because that’s all it knows how to do, suffocatingly tamped down by the sociopathic veneer of English politeness. It’s haunted me since the day I watched it.

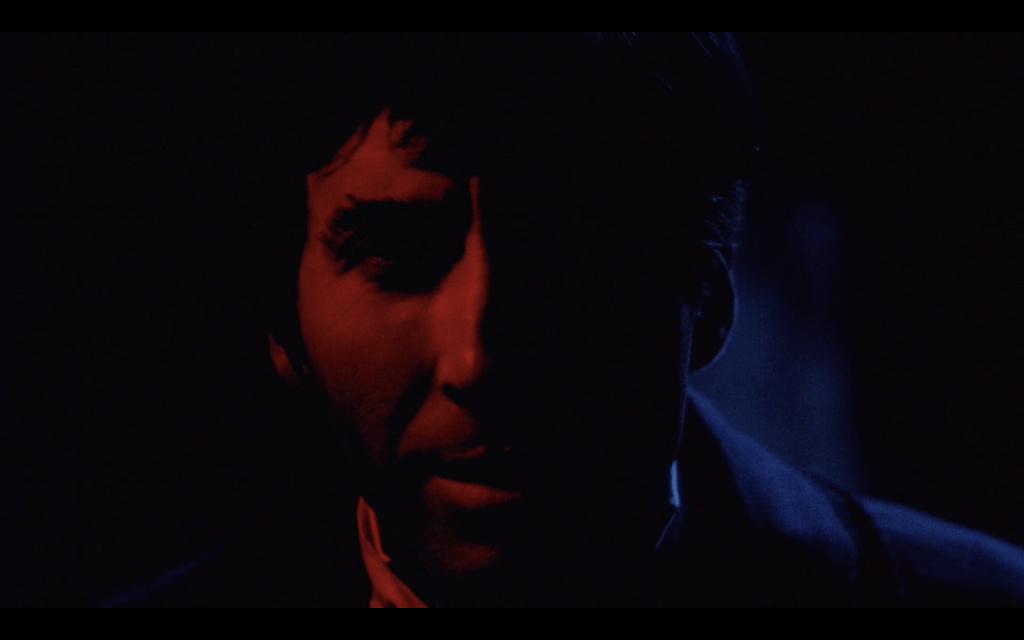

26. The Whip and the Body (Mario Bava, 1963)

Gothic giallo, an S&M ghost story. Bava locates the pull of temptation and guilt in each track of the camera, rendering fear, desire and pain in one of cinema’s most sumptuous plays of color and shadow. Still, it doesn’t seem right that Christopher Lee’s character is named Kurt. I can’t imagine being scared of a Kurt.