It’s the electrifying conclusion! Before we finish I’d like to shout out Filipe Furtado, God of Letterboxd, as well as the great Dave Kehr, the two people whose critical sensibilities and recommendations likely shaped this list more than anyone else. When I look at these pictures all in a row I see 25 masterpieces that enriched my life a great deal, and hey, isn’t that why we’re all here?

25. Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (Frank Tashlin, 1957)

It seems fitting to start this off with another confession: this is the first Tashlin film I’ve seen. I blame TCM! Anyway, it’s hard to imagine anyone today cooking up a genuinely hilarious satire of the advertising world without once lapsing into obviousness or scolding, but Tashlin pulled it off. I don’t even want to think about the probability of any comedy director matching his formal skills. Features an all-time great cameo at the end as well.

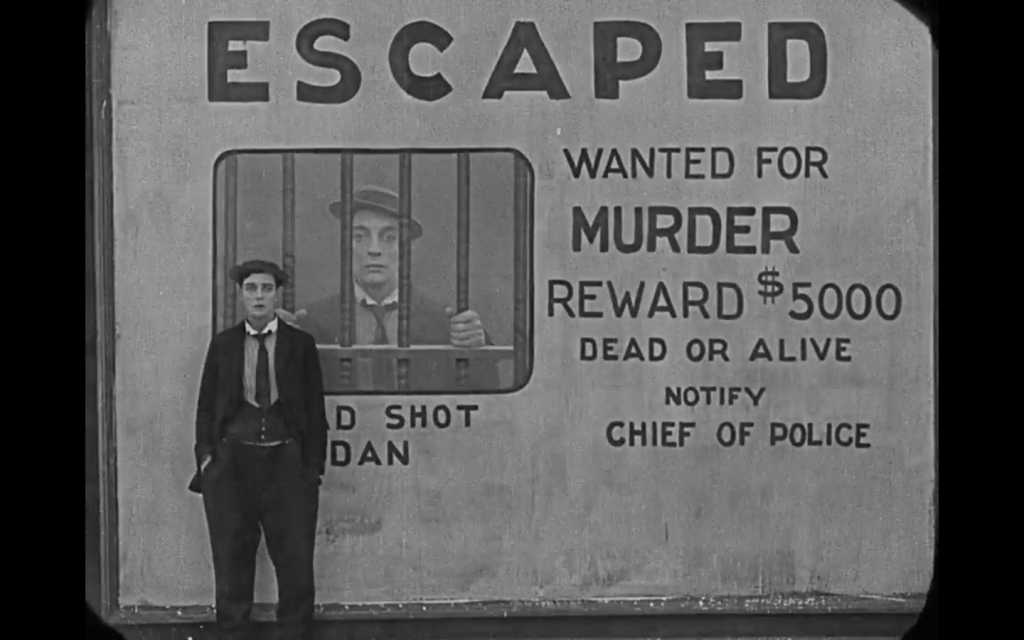

24. “The Goat” (Buster Keaton, 1921)

It’s probably bad that this is the only short on here (technically- there were two in between 40-60 minutes), but if you’re going to save it for one person it should be the GOAT. This is my favorite of Buster’s shorts, in no small part because it features the most cop humiliation of any of them, somehow even including “Cops.” Buster running away from people is like Gene Kelly dancing or Chow Yun-Fat dual-wielding. You simply cannot be unhappy while watching it.

23. Kansas City Confidential (Phil Karlson, 1952)

The first ingredient is one of the all-time great crime film screenplays, a miracle of innovative structure, constantly surprising plot turns, dramatic irony and interlocking character-driven tensions. The second ingredient is Phil Karlson’s direction, so bruising and bare-knuckled it feels like the camera is going to start taking swings. The third and fourth ingredients are Lee Van Cleef and Jack Elam. The result is one of the best noirs ever made.

22. A Better Tomorrow (John Woo, 1986)

“I believe in my world. I believe in brotherhood and everything that goes with it.”- John Woo

That belief is often what separates the great artists from the merely proficient. In John Woo’s case, it’s a belief in brotherhood as well as blood squibs. Today’s action directors need to take note.

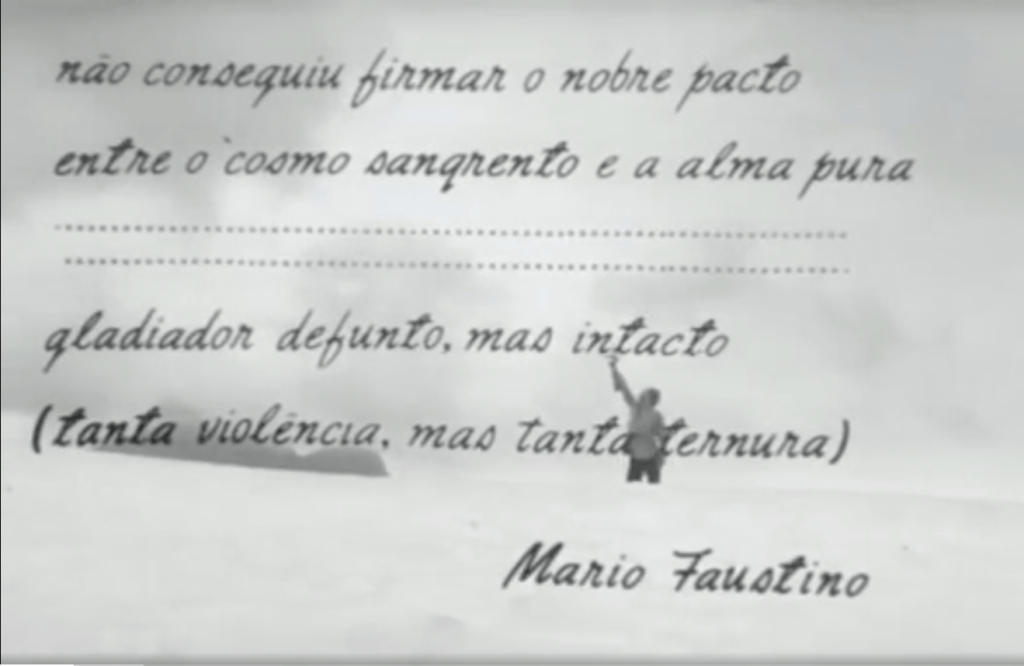

21. Entranced Earth (Glauber Rocha, 1967)

Probably the film on this list I’m least qualified to talk about, and as a result I’m sure a lot here went over my head. Even so, this was as intellectually stimulating as anything I watched this year, but nothing this angry or intense could ever feel like homework.

20. The Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting (Raul Ruiz, 1978)

I guess I could talk about everything this movie has to say about representation and interpretation, its levels of satire, or the depths of its imagination. The truth, however, is that I just want to watch these camera movements all day.

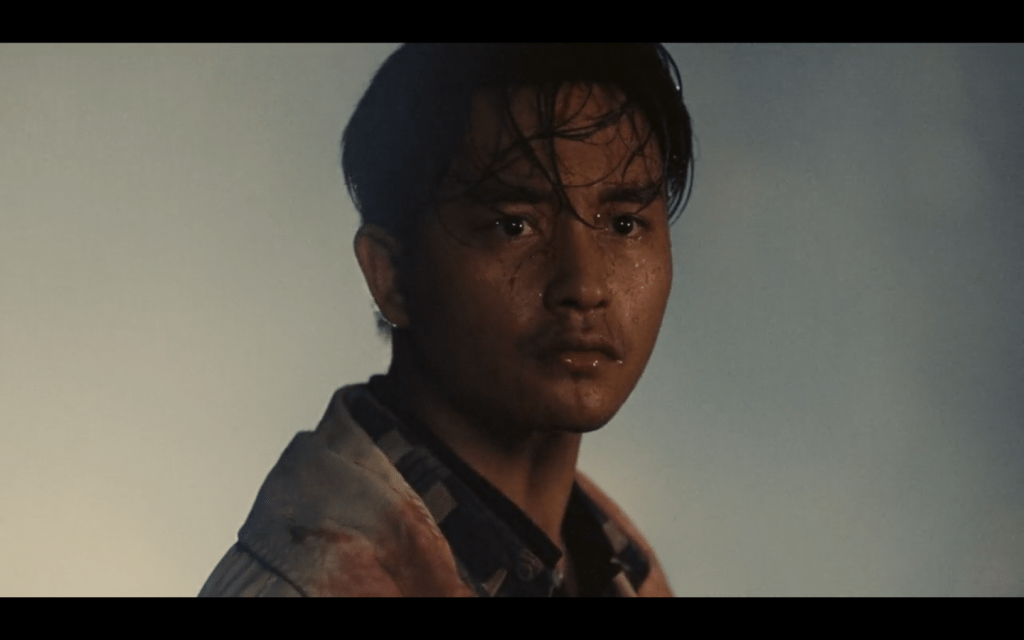

19. Once Upon a Time in China (Tsui Hark, 1991)

The great Chinese folk hero Wong Fei-Hung and friends take on English imperialists, American slave traders, Chinese cops, a band of gangsters, and a rival kung-fu master at the same time. Jet Li kills a guy by flicking a bullet into his forehead, while Jacky Cheung runs around looking exactly like Johnny Depp in Dead Man. Pretty much everything you could want from a movie.

18. Horse Money (Pedro Costa, 2014)

It’s surprising that this is my favorite of Costa’s Fontainhas series of docufiction films, as my general lack of knowledge about Portuguese history has always been an obstacle to my understanding of them and this one may be its most historically-focused entry. Even so, the violence and despair that echoes through its last 40 minutes have stayed with me like little else this year, and I felt that Costa’s impositions of fiction have never been so richly associative. Its followup, Vitalina Varela, is now my favorite film of 2020.

17. Pennies From Heaven (Herbert Ross, 1981)

Having sung the praises of Dave Kehr in my intro, I’d now like to take issue with his review of this movie. Kehr considers the film’s sole idea to be “the discovery (less than original) that musicals don’t reproduce social reality.” While that’s certainly an important element, it’s just as essential to note how the songs (recordings from the ’30s lip-synched by the actors) provide the characters with a mode of expression that’s otherwise unavailable to them, an avenue of escape that’s ultimately a dead end, but an escape nonetheless. It’s a complex and considered deployment of the gimmick, from Gordon Willis’ Hopper-based cinematography to the way any potential tawdriness is tempered by protagonist Steve Martin’s sex-crazed idiocy.

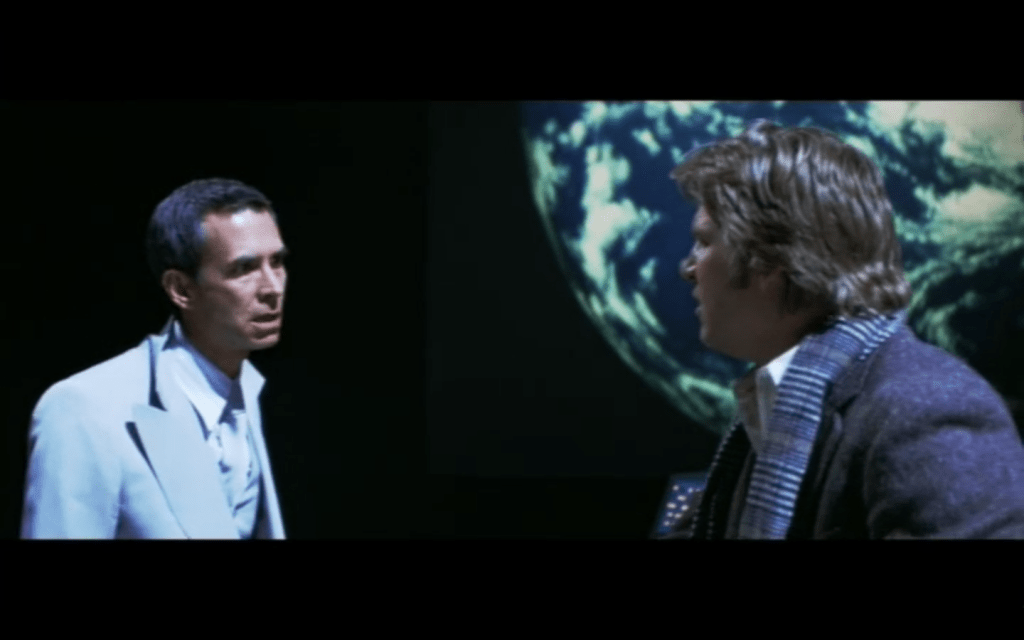

16. Winter Kills (William Richert, 1979)

A thrilling, hysterical, deeply paranoid and constantly escalating alternate secret history of the Kennedy assassination featuring one of the greatest and weirdest casts in movie history. I have to assume the only reason we’re not all talking about this movie all the time is that it’s been suppressed by the deep state for getting too close to the truth.

15. Wendy and Lucy (Kelly Reichardt, 2009)

WARNING: do not watch this movie at work. You WILL end up crying at your desk and having to hide it from your coworkers. I speak from experience.

14. Rosa la Rose, Public Girl (Paul Vecchiali, 1986)

Pure sensory pleasure in service of a story about searching for something more than that. Vecchiali conjures the ghosts of Ophuls, Demy and Von Sternberg to create a world that’s as seductive as it is acrid, a musical delight cast over with the pall of death from its all-time great opening shot to its all-time great final shot. Marianne Basler…………. hello.

13. The Day I Became A Woman (Marziyeh Meshkiny, 2000)

Three tales of Iranian women, each at different stages of life, each attempting to assert themselves in the face of a hostile world. I wish all political cinema shared the brilliant imagination Meshkiny displays here, especially when combined with such a deft formal touch and detailed sense of character. It elevates her style from easy allegory to genuinely inspired political image-making. The second story is both particularly magnificent and highly reminiscent of a Brisk God video.

12. Dangerous Encounters of the First Kind (Tsui Hark, 1980)

I watched two films by Hong Kong’s cinematic kingpin this year, and as such he’s the only filmmaker taking up two spots in my top 25. This early punk film is one of the most volcanically nihilistic ever made, but Tsui is too multifaceted a filmmaker to turn it into misery porn. Perverse humor and skewed sentimentality exist alongside blinding rage, making the ugliness of its vision that much more all-encompassing. Please consult before ever calling Gen-Z “hardcore” again.

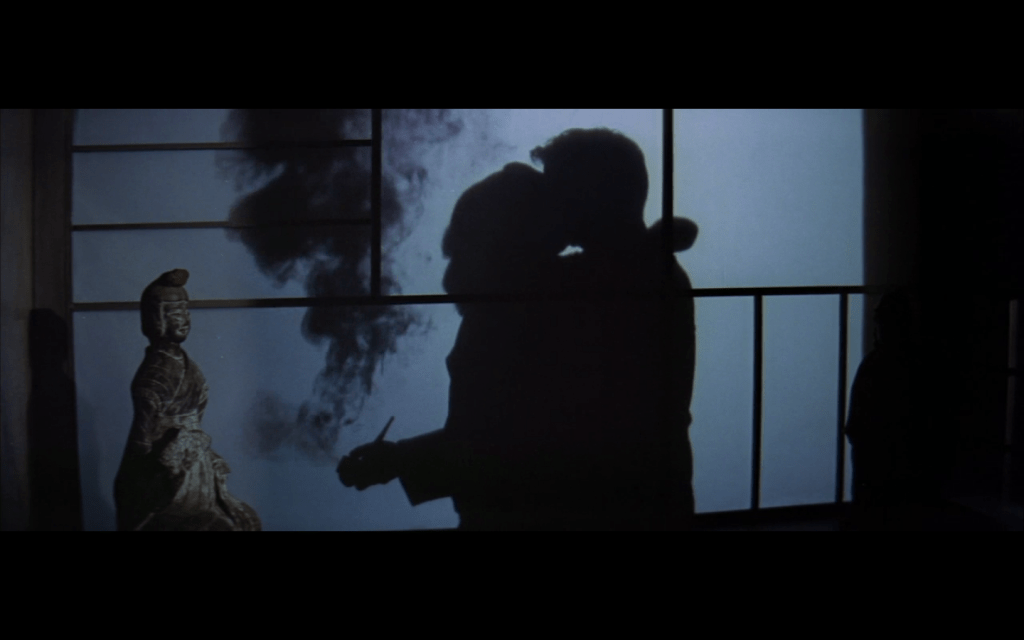

11. The Crucified Lovers [aka A Story From Chikamatsu] (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1954)

I probably should have seen more Mizoguchi by now, considering he’s one of my favorite filmmakers ever (real original, I know), but the fact is that they’re kind of too overwhelming for me to watch more than once in a great while. This one combines many of his usual concerns- forbidden love, class differences and gendered oppression- in moving from a complex social structure to a sublime harmony with nature. An object lesson in how to make a simple story so much more.

10. Vampyr (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1932)

Note to rich failsons everywhere: If you agree to fund movies by world-historical masters of the medium, like the French aristocrat Nicolas De Gunzburg did for this, you will be immortalized in a way that no amount of investing in startups that help people auction off their plasma or whatever ever will. I know you don’t care, but the world will be richer for it as well. If you will also only do it in exchange for playing the lead role, this is a good example of a movie where your complete lack of talent or charisma won’t be much of a liability. You can even use an alias! He did! It’ll be fine!

9. The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (Preston Sturges, 1943)

Look… I watched this movie on February 13th, and I didn’t write a word about it then. It’s not easy to start writing about a movie ten months after you see it. Just trust me that it’s a delight, and Betty Hutton is on fire throughout.

8. Only Yesterday (Isao Takahata, 1991)

A walk through histories, of the mind and the land. Takahata takes detours into Americanization, agricultural politics, sexual awakenings, slumming, and so much more, the richness of his world elevating the personal travelogue into such a tender, sublime melancholy. This possesses a sense of reverent beauty and patiently accumulated detail worthy of Ozu and Naruse (not to mention other Ghibli works), while staying just as resistant to simplistic sentiment. The happy ending can’t erase the deeper heartache underlying everything that came before- the realization that the memories that will stay with you most vividly are invariably the most embarrassing, painful and damning.

7. Sparrow (Johnnie To, 2008)

Few movies have ever floated like this. Only a born filmmaker like To could pull off the combination of casual formal perfection, sweetness, humor and suspense he achieves here. As always, To sublimates emotion into pure movement, but here it hits a newly joyful high.

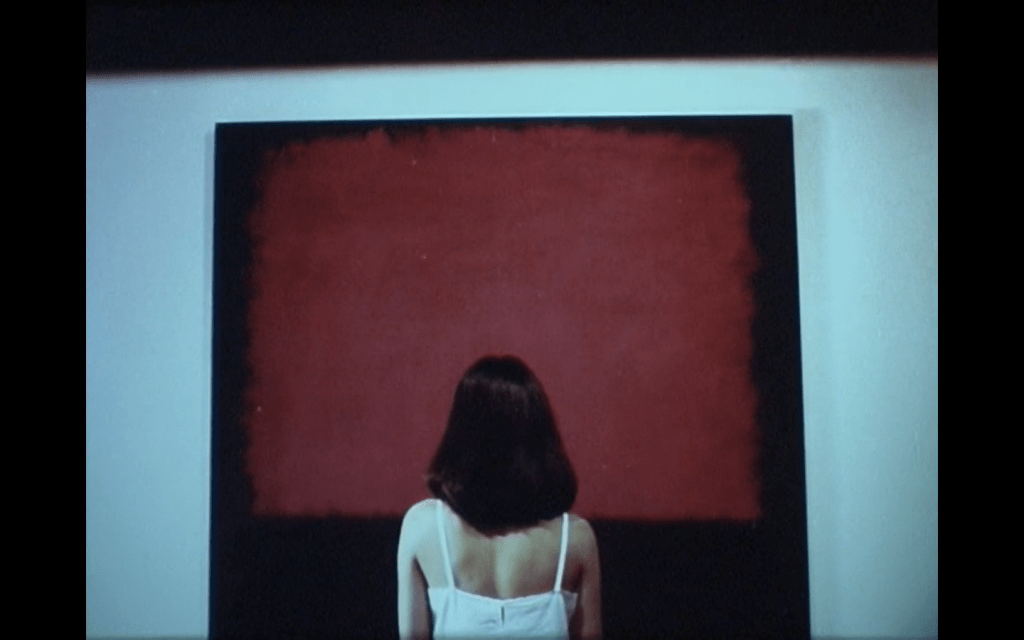

6. Love Massacre (Patrick Tam Kar-Ming, 1981)

It opens with an obvious reference to Von Sternberg’s Morocco, and what follows is a work every bit as richly imagistic as that master at his best. But where Von Sternberg’s frames were humid, densely layered latticeworks, Tam’s visual reference points move from classical Hollywood to the abstract modernism of Mark Rothko, the clean lines and bold colors illuminating a spiritual emptiness that comes with both loss and dislocation. Tam composes every shot with precision and imagination, a simultaneously florid and severe style every bit as sui generis as an American-set, Cantonese-language slasher art film would suggest. The greatest bolt from the blue I had this year.

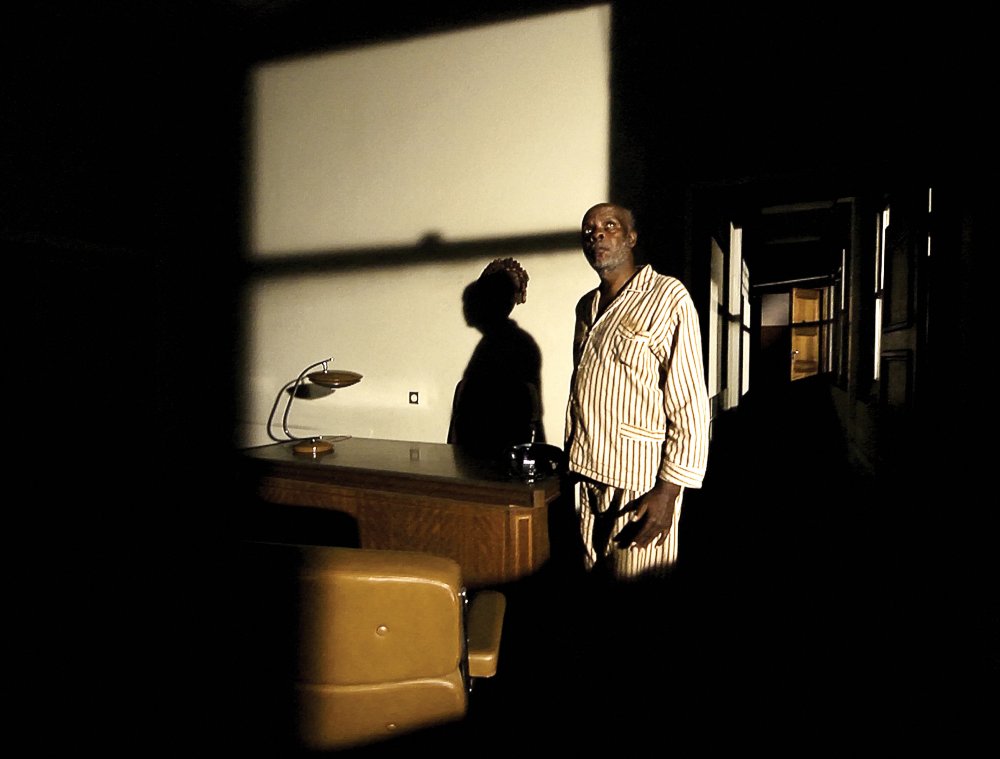

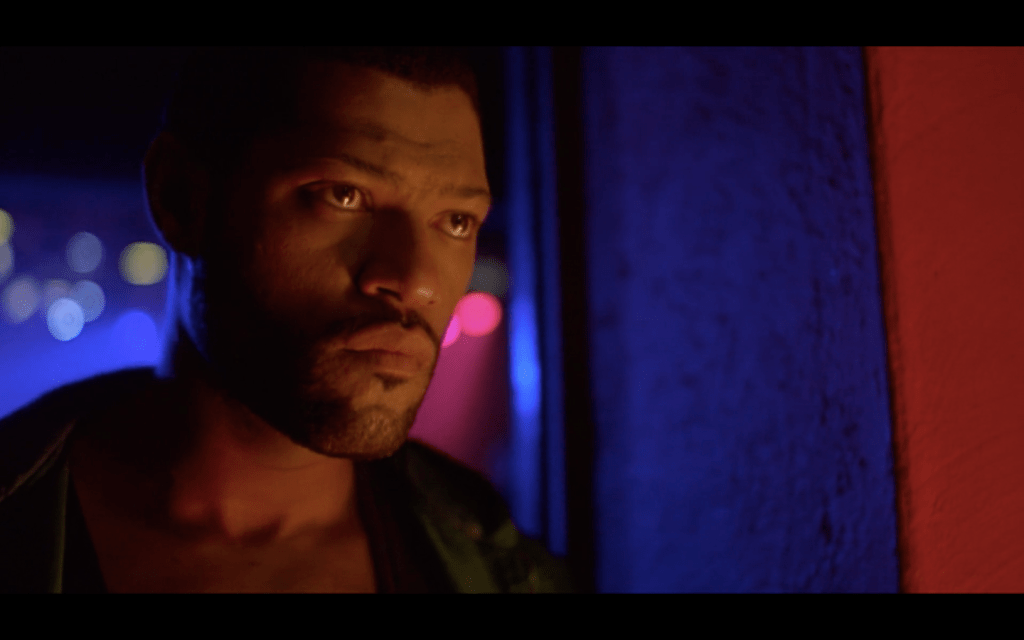

5. Deep Cover (Bill Duke, 1992)

A movie I feel I could write about forever, and one of the most radical ever released by a major studio. This is a movie that, during the Bush 41 era, calls out the president by name in its story about the CIA and FBI acting as a cartel for Manuel Noriega, selling drugs to impoverished black communities to serve the dual purpose of funding their covert operations and decimating those communities. Deep Cover would be remarkable if that political potency was all it had going for it, but it’s only one element of the film’s greatness. Bill Duke’s direction carries a brutally expressive poetry from the first shot, and Laurence Fishburne, playing a character mired in crises of morality and identity at every moment, gives one of the most complex and wounded lead performances of the era. The joke I made about Winter Kills might actually be true with this one.

4. Hellzapoppin’ (H.C. Potter, 1941)

Hellzapoppin’ has developed a reputation (not nearly enough of one, but a reputation nonetheless) for being one of the most mind-meltingly deranged, inventive and hysterical comedies ever made, and it certainly is that. What is hasn’t yet developed a reputation for, as far as I can tell, is its genuinely political vision of a cinema freed from all bounds of creative restraint, narrative requirements or even basic logic, one that spans from the inclusion of Black performers (blowing their white counterparts off the screen, of course) to tampering with the basic DNA of film grammar. I basically couldn’t believe what I was seeing the entire time, but its ultimate surprise was something else entirely: it moved me.

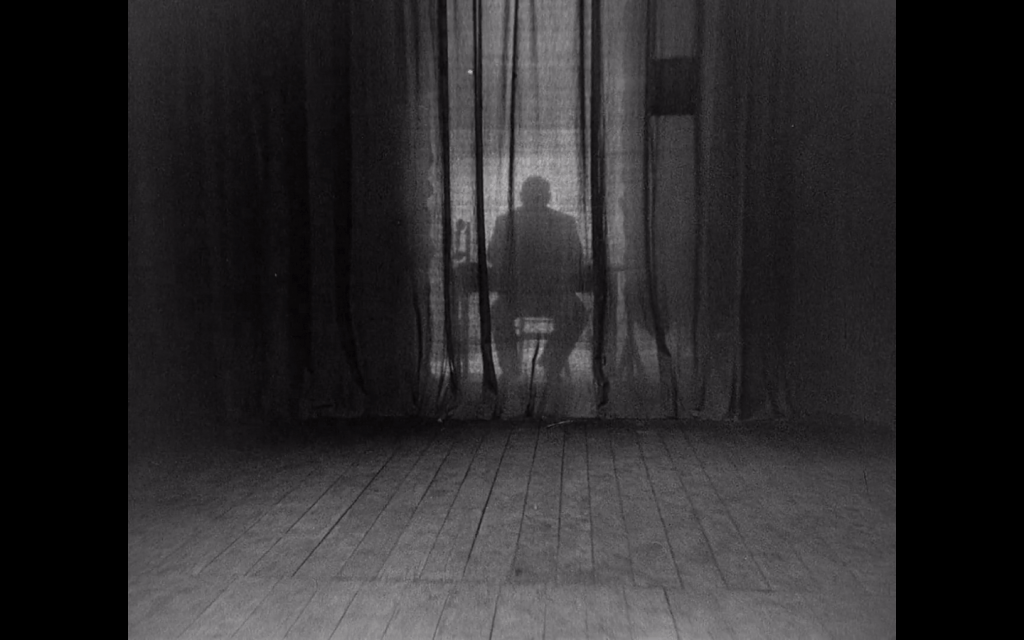

3. The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (Fritz Lang, 1933)

The ranking of this movie, the last one Lang made in Hitler’s Germany before fleeing, may have something to do with the utter failure of artistic institutions to meaningfully confront the Trump Era. This sequel to Lang’s earlier silent epic Dr. Mabuse the Gambler turns that film’s mystical secret criminal society into a direct parallel for the Nazi regime, even writing some Nazi slogans directly into his villains’ dialogue. But where that could potentially result in a facile, narrow allegory, Lang instead expands the film into a terrifying moral vision of a society rotting from the inside. The severity of his images strips every turn of the labyrinthine narrative down to its barest moral truth, where no barriers remain between the ultimate evil and the deepest recesses of our souls. Truly, deeply chilling stuff.

2. Life, and Nothing More… (Abbas Kiarostami, 1992)

There’s a moment here- when an unseen mother reaches an arm into the frame and tells the main character’s son to give her child the rest of his soda- that encapsulates so much of what makes Kiarostami’s films so beautiful. They feel so expansive and open despite their tightly ordered images because those images are so teeming with life at their edges, constantly suggesting the entirety of the human experience lies just offscreen. The boundaries of each frame are rigidly defined, which means each incursion into one is meaningful- to cross into a frame in Kiarostami’s cinema is to reach across generations, across social backgrounds, to forge a connection through expanding the scope of who the movies see and listen to. Every gesture carries a rare depth of meaning, each one stripped down to the essence of human interaction. Kiarostami’s films are so moving because they aren’t just humanist, they represent a uniquely humanist reimagining of the fundamental formal possibilities of cinema.

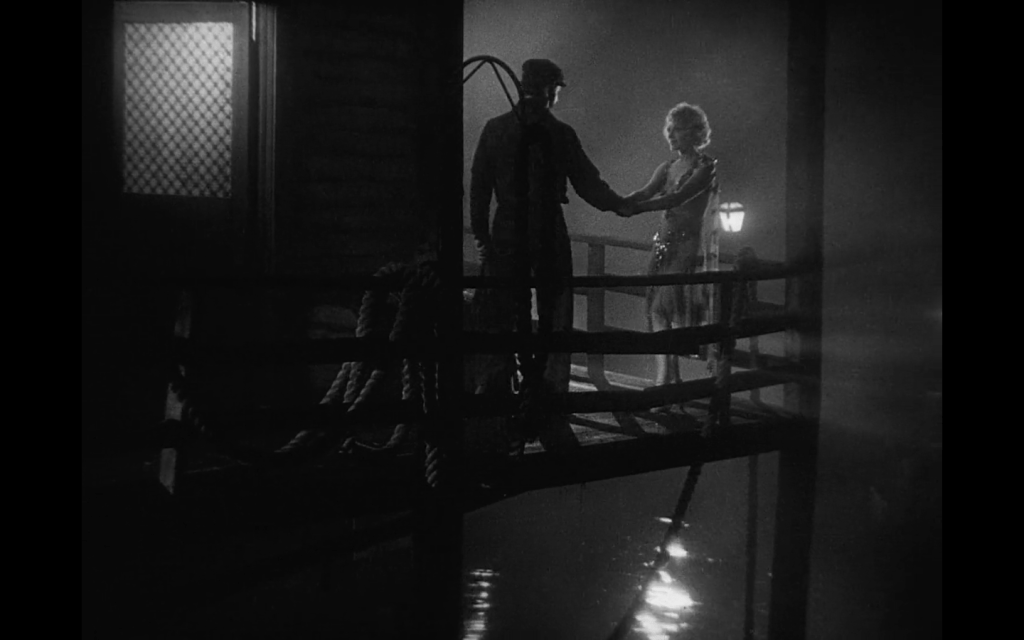

1. The Docks of New York (Josef von Sternberg, 1928)

For the second year in a row, von Sternberg takes the cake (last year’s top pick was Dishonored). Much like Mizoguchi, I’m not capable of handling von Sternberg with any regularity; I feel like what makes his work so overwhelming is his ability to concentrate seemingly every element of great cinema into each frame: physicality and artifice, beauty and dissonance, despair and hope, a romantic belief that exists in an eternal present tense, always slipping away even as it builds to an unbearable poignancy. The story here, of a sailor and prostitute on the Lower East Side who get married for laughs, only to inevitably fall in love, is as barebones as it gets. But no filmmaker has ever made so much out of so little, in no small part due to an atmosphere as thick as any ever captured on film. Never before have I felt such a clear sense that the movie camera was reanimating the long-dead people onscreen, as though the images were a miraculous portal between past and present. Von Sternberg doesn’t shy away from melodrama but there’s nothing easy about its sentiments- “I’ve never done a decent thing in my life,” George Bancroft’s sailor boasts, lest we feel tempted to romanticize him. Still, by the time von Sternberg makes the palpable emotional investment of his gaze explicit by literally shooting a close-up from the clouded POV of a tear-filled eye, it’s clear that we’re in the hands of one of the most romantic of all filmmakers. Von Sternberg’s characters tend to hold onto their desires up to and beyond the point of madness, damnation and death, but even as this ends with a prison sentence there’s an ultimate triumph of hope. True happiness is still slightly out of reach, and who knows if it’ll ever come, but hope is the best the movies can offer us. Whenever I think about why this film has remained at the top of this list since I started it, I think of the scene where the two are married in a sailor’s dive, one of the most sublimely beautiful in the history of cinema. It’s as enveloped in smoke, beer and the communal joy of the bar patrons as it is in the unspoken longings of its main subjects, and one gets the feeling of a group of people reaching towards transcendence under the most modest and disreputable of circumstances. If the movies have a nobler pursuit than pushing us toward that transcendence, I’ve yet to encounter it.