To get technicalities out of the way- this goes by U.S. commercial release date, and I understand why many people object to that method. It’s always a little confusing, and the lines are especially blurred in this year of all-virtual festivals, but the simple fact is that I’m not a professional critic, and as such I wouldn’t be able to finish my lists for most years until well into the next year if I went by worldwide festival premiere. The most important thing, though, is that I’m not one of those people that blurs both together at will- for example, putting First Cow, which premiered at NYFF in 2019 and publicly in 2020, on the same list as Days, which premiered at NYFF in 2020 and will publicly in 2021. I understand that I’m the only person who cares about this, but it irks me.

Anyway, this list got a little more conventional as time in the year ran out, which is unfortunate, but I still think it’s just unique enough to justify writing about it. It gets more interesting toward the top, so don’t give up. I promised in my other end-of-year list that I wouldn’t waste your time with truisms about 2020 as some sort of sentient being, and with that in mind let’s get started.

Unseen: Nomadland, Tommaso, Heimat is a Space in Time, City Hall, Mangrove, The Traitor

15. The Assistant (Kitty Green)

The subject matter of documentary filmmaker Kitty Green’s narrative debut has been all but inescapable over the past three years, and such timeliness has a tendency to result in pandering PSAs a la Bombshell. Where Green makes her mark is in envisioning the entire world as an office- late capitalism’s total sublimation of the self into careerism and financial incentive- making the drama of her film not just one of workplace gender dynamics but of how misogyny and gendered abuse have persisted in modernized spaces and “progressive” industries. Even if its social commentary is didactic at times, its images of total entrapment in corporate structures, sealed off from any world beyond them, are difficult to shake.

14. Martin Eden (Pietro Marcello)

The first half of this movie, so rich with intellectual discovery and with a flowering, tactile aesthetic that perfectly communicates an expanding internal life, is among the very best things I’ve seen this year. Unfortunately, I found that it became far more narratively and thematically muddled in its second half, in which its titular autodidactic literary sensation curdles from a righteous working-class firebrand into an incoherent “individualist.” Still, the richness of its view of history unmoored from time and in a constant state of transformation, along with Luca Marinelli’s starmaking performance, guarantees it a spot.

13. Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets (Turner Ross, Bill Ross IV)

The concept of a documentary about a ragtag group of weirdo bar patrons sending off their imminently closing second home with a final night of celebration and lament seems too perfectly suited to me to be true. Because I’m glad I didn’t read too much about this movie before seeing it, I’ll hold my tongue as to whether it is. But true or not, the perfect social dynamics captured by the Ross brothers’ simultaneously raw and dramatically potent camerawork and editing, along with their poignant tribute to the weird and wonderful corners of the world being bulldozed by a world of corporate consolidation, is endlessly moving.

12. Never Rarely Sometimes Always (Eliza Hittman)

I suppose comparisons to The Romanian Film Which Shall Not Be Named were inevitable, but as far as I’m concerned they only serve to highlight how much more complex Hittman’s approach is, even if it might seem simpler. That other film’s severe, ostentatious style ended up replicating the oppressive weight of the world it portrayed more than meaningfully critiquing it, turning its characters into vessels for commentary and hypocritically stripping them of their own agency (not to mention vacuum-sealing them in the past). Hittman, on the other hand, remains in a constant present tense, at every moment immersed in her central pair’s relationship to the world around them and to each other. The subjectivity of her style allows the (let’s face it, relatively simple) social commentary to constantly increase in scope and emotional force by nothing more than the accumulation of detail, a far more challenging and rewarding strategy than the directorial announcement of Big Statements. Stars Sidney Flanigan and Talia Ryder both do terrific work that functions perfectly with the register that Hittman works in, the facts of the world so ingrained even at a young age that nothing needs to be spoken but still carrying a sense of youthful discovery and disappointment. I guess my full Sundance moratorium will have to wait.

11. Bacurau (Kleber Mendonça Filho, Juliano Dornelles)

The most satisfying movie of 2020. This is basically a feature-length adaptation of that failed private contractor coup in Venezuela, and what makes Bacurau so effective is the filmmakers’ understanding that accurately capturing the evil of imperial military forces requires portraying them as monsters so inhuman that they literally feel like aliens, made clear by their UFO-like drones. It’s nice to have proof than an incisively political genre movie that doesn’t condescendingly feel the need to “elevate” itself into prestige territory to get its point across can still exist.

10. Dick Johnson is Dead (Kirsten Johnson)

It’s pretty self-evident that the central conceit of Kirsten Johnson’s documentary- staged scenes of her Alzheimer’s-stricken father Dick coming to a variety of violent ends- end up being much more about their production and Dick’s role in them than the actual filmed products themselves, and I don’t know that they have much to say about the representational or therapeutic potential of cinema (nor do I know if that’s what Johnson was going for). More often they serve as an impetus for filmmaker and father to directly confront the idea of his death. Going further, the fully artificial scenes of Dick passing into the afterlife are a glaringly incongruous misstep that feel like a concession to movie-selling gimmickry. But I disagree with the contention that it should have just been a straight, No Home Movie-esque diary film- I think its plays with time and fiction are essential by the end, and its final idea of Dick being simulataneously “dead” and “alive” both before and after his actual death is one of its most moving.

9. First Cow (Kelly Reichardt)

Beautiful stuff from one of America’s very finest filmmakers, but let’s be honest: I was hoping for more cow. The cow was good and could have had a much larger role. That being said, John Magaro and Orion Lee give two of the year’s best performances (Lee would be my Best Supporting Actor pick), so the humans aren’t half bad either.

8. Shoot the Moon Right Between the Eyes (Graham L. Carter)

That comment about Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets feeling specifically directed towards me applies to this, a musical comedy about two aging con men lamming it through the bars and motels of Texas to the songs of John Prine, even more (obviously, I really miss bars). Like that other film, this one also carries an added tragedy with the death of the great, life-affirming songwriter it pays tribute to. A picture that perfectly captures the feeling of a crying-in-your-beer country song, always reaching out for moments of connection made impossible by a life on the road. The gorgeous Technicolor-gone-digital cinematography by Carmen Hilbert is one of the year’s great surprise contributions.

7. The 7th Annual Live ‘On Cinema’ Oscar Special (Eric Notarnicola)

The debate over which moving image works do or don’t qualify as “movies” is so tedious and meaningless it drove me off social media this year, so if you have any complaints about this being on here take them elsewhere. This year’s edition of everyone’s favorite codependent psychopaths discussing the Oscars in real time took the shape of Tim Heidecker’s marriage to former campaign manager and current business partner Toni Newman, throughout the entirety of which everyone in the building is slowly being poisoned by the exhaust fumes of Gregg Turkington/The Joker’s running car. Gregg’s wedding speech, in which he can’t bring himself to communicate through anything other than movie titles even after Tim called him his “oldest friend,” was one of the most genuinely painful things I’d seen in a long time. Then I watched an agonizingly protracted tableau of already-empty husks of people being slowly drained of what little life they have left, the innocents that they’ve roped in doomed to the same cruel fate. The pure reality-breaking derangement of the last 30 minutes tapped into the madness and despair of our world like nothing else on this list, and in a way it’s the only entry on here other than #1 that had a shot at the top spot.

6. The Portuguese Woman (Rita Azevedo Gomes)

The obligatory “I didn’t understand this movie but I’m pretty sure it’s great” entry. I won’t deny that this wasn’t the easiest 136 minutes I spent in 2020, but its portrait of rotting aristocracy and eternal, self-sustaining warfare for its own sake have only grown in my mind since I saw it. Gomes’ eye for detail, light and color within her distant, flatly composed frames is remarkable, and goes a long way towards bringing life to its heady literary ambitions.

5. The Man in the Woods (Noah Buschel)

Twilight Zone/Roswell-era sci-fi mysticism and secret histories in search of narratives lost and found, its conspiratorial tendencies used both in service of and against power. The most bafflingly underseen (at this point, all but unseen) film of 2020, as its gorgeous black-and-white photography, hushed sense of commingled wonder and danger, and the interactions of its great cast are all immensely enjoyable. Just so vividly crafted, playful but plaintive, a potentially preachy narrative given a life and mystery of its own. Buschel understands that gently falling snow or the light spilling out a window can be just as meaningful as his florid dialogue. Its resolution doesn’t go much of anywhere story-wise, but it hardly matters when a film absolutely enraptures you from the first frame to the last.

4. To the Ends of the Earth (Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

The filmography of Kiyoshi Kurosawa, one of the greatest of any living director, is rife with stories that begin intimately and constantly expand, the psychoses or dangers suffered by one person slowly taking hold of the world around them. His latest film, by contrast, is all about the sharp delineation between its main character (TV travelogue host Yoko, played by Atsuko Maeda) and the world she traverses (Uzbekistan). Kurosawa channels a visceral feeling of dislocation and utter aloneness for his fish-out-of-water tale, his deft, negative space-heavy widescreen compositions always thick with the terror of the unknown. But of course, this is all preamble to the final world on the picture.

3. Fourteen (Dan Sallitt)

A small-scale tale of two friends that distinguishes itself through the surprising width of its scope, spanning several years and vast changes in the lives of both of its subjects. Tallie Medel as the sensible Mara and Norma Kuhling as the unstable Jo both take their place among the year’s best performers, nailing the sense of personal history and of gradual divergence from each other that Sallitt’s carefully calibrated yet audacious script requires. At a time when the timidity of American indie cinema results in such consistently limited ambitions, seeing a film as small as this with such a willingness to take narrative risks is enormously rewarding, especially when those risks pay off as well as they do here.

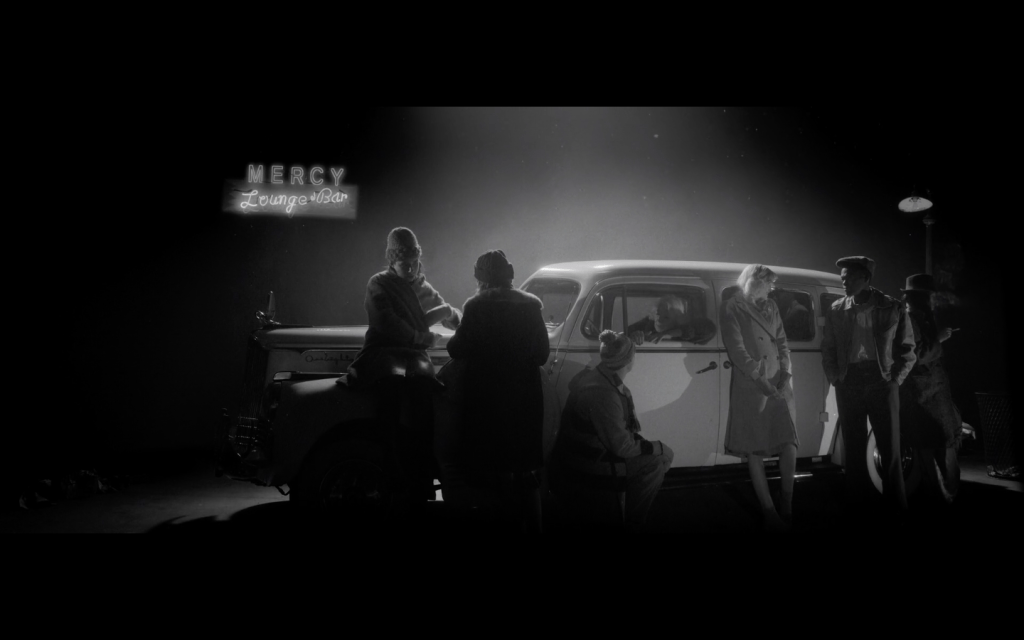

2. The Wild Goose Lake (Diao Yi’nan)

I saw Diao Yi’nan’s followup to his festival circuit breakout Black Coal, Thin Ice at the New York Film Festival way back in October 2019, which is one of the perils of using commercial release dates to make these lists as I do. To be completely honest I couldn’t recall the plot to you in much detail, but such things are unimportant compared to Yi’nan’s achievements of atmosphere and societal portraiture. The Wild Goose Lake shares its predecessor’s knack for deadpan violence, neon stylings and focus on the injustices borne by women in contemporary China’s police state while expanding into a more wide-ranging nocturnal odyssey through the abscesses of authoritarianism. I’ve seen it compared to the work of Fritz Lang, and Yi’nan’s talent for replicating the crushing weight of authority with labyrinthine narrative and visual structures more than justifies the compliment. Nowhere is that more apparent than in the finale, a feat of large-scale choreography akin to a pulp ballet, including a sick umbrella murder. Here’s hoping that Yi’nan remains able to pack such potent political ideas into his censor-skirting genre exercises.

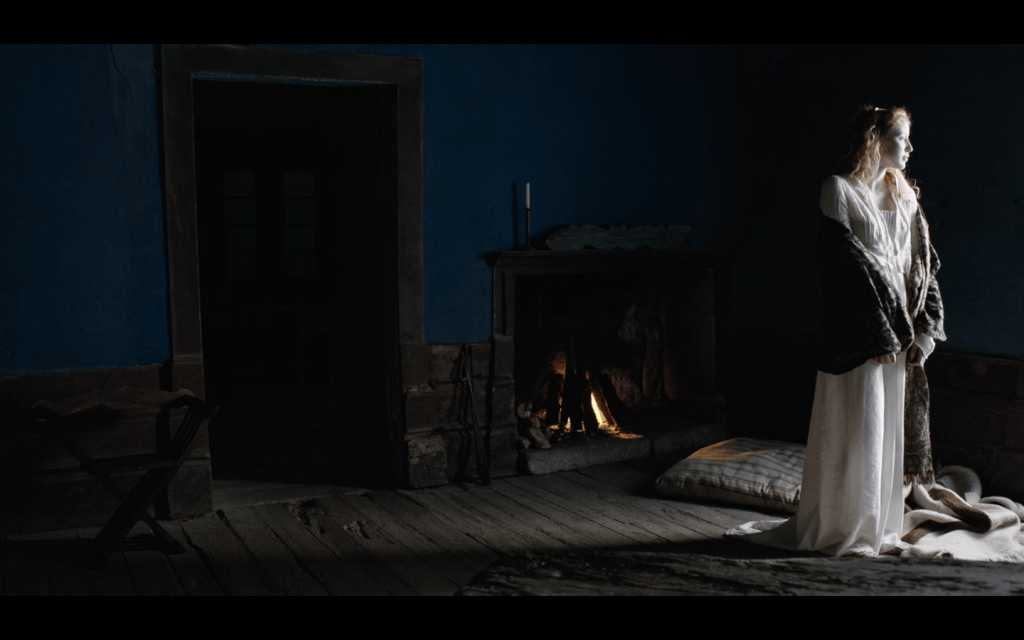

1. Vitalina Varela (Pedro Costa)

A woman arrives on a plane and steps onto a deserted tarmac in the dead of night, the monumental framing, montage and lighting suggesting that the earth trembles under her feet. Vitalina Varela, only days after the death of her husband, has returned to the crumbling Fontainhas district of Lisbon from her home of Cape Verde, determined to work her way through her husband’s life and secrets. The fifth of Pedro Costa’s series of docufiction films has been referred to as its simplest and most “accessible,” which is true in a way- it hones in on a single character and narrative in a way that the other Fontainhas films, more grounded in history or in tangible experience, have not. But that’s not to say that Costa’s gift for poetics or complex associations between the personal and political have dimmed- if anything, they’re as movingly concentrated into a central idea than ever. More than any other working filmmaker, Costa carries the influence of the silent masters into the 21st century, and his particular preoccupation with synthesizing their influence into the advent of digital technology reaches some of its most sublime highs here. Vitalina Varela combines Griffith’s sense of montage and composition with Murnau’s facility with light and shadow, this time around dispensing with the blurry DV of earlier Fontainhas films in favor of a crisp digital aesthetic that brings its title character’s unforgettable face and haunted eyes into sharp focus. The result is arguably the creation of more breathtaking compositions than the rest of the films released in 2020 managed put together, infusing its walk through personal tragedy with a mythic, purely cinematic import. The night world that the film occupies is nothing new for Costa, which is what makes its denouement, marked by both death and the feeling of having arrived on the other end of a long, dark night of the soul, the most revelatory cinematic sequence of the year. Vitalina Varela is an achievement that could only come from decades of personal investment at level of supreme artistry, and endlessly reassuring reminder of cinema’s limitless potential at a time when believing in such a thing feels nearly impossible.